The Evolution of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) have been a cornerstone of web accessibility efforts for over two decades. Developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), these guidelines aim to ensure that websites and digital content are accessible to all users, including those with disabilities. As technology and user needs have evolved, so too have the WCAG standards, leading to significant updates and revisions. This blog post delves into the evolution of WCAG, comparing the key features, strengths, and limitations of WCAG 1.0, WCAG 2.0, WCAG 2.1, WCAG 2.2, and the upcoming WCAG 3.0.

WCAG 1.0: Laying the Foundation for Web Accessibility

The Emergence of WCAG 1.0

WCAG 1.0, released in May 1999, marked the beginning of a formalised approach to web accessibility. At the time, the internet was rapidly expanding, but considerations for accessibility were still in their infancy. The development of WCAG 1.0 was driven by three converging trends: the increasing importance of telecommunications, growing political awareness around the rights of individuals with disabilities, and the expanding role of the web as a critical informational platform (Ellcessor, 2010).

WCAG 1.0 was essentially a response to the need for a standardised set of guidelines that web developers could follow to make their content more accessible. It was a community-driven effort, informed by feedback from early adopters and accessibility advocates. The primary objective of WCAG 1.0 was to provide a straightforward checklist that developers could use to improve the accessibility of their websites, particularly for users with known physical disabilities such as blindness and deafness.

Key Features of WCAG 1.0

WCAG 1.0 was structured around 14 guidelines, each accompanied by specific "checkpoints" that outlined the minimum requirements for accessibility. These checkpoints were designed to address common barriers faced by users with disabilities, and they provided clear instructions on how to make content accessible.

The guidelines covered a wide range of topics, including:

- Text Equivalents: Providing text alternatives for non-text content, such as images, so that users relying on screen readers could access the information.

- Colour and Contrast: Ensuring that information conveyed with colour was also available without it, making content accessible to users with colour vision deficiencies.

- Navigation: Designing websites that could be navigated using a keyboard, catering to users who could not use a mouse.

One of the strengths of WCAG 1.0 was its simplicity. The checklist format made it easy for developers, many of whom were not familiar with accessibility issues, to understand and implement the guidelines. The authors of WCAG 1.0 also provided suggested techniques to help practitioners achieve the checkpoints, which was particularly important at a time when accessibility was a relatively new consideration in web development.

Limitations of WCAG 1.0

Despite its groundbreaking nature, WCAG 1.0 had several limitations that became more apparent as the web and its user base evolved. One major limitation was its narrow focus on specific, well-defined physical disabilities. While this focus was understandable given the context in which WCAG 1.0 was developed, it meant that the guidelines did not adequately address the needs of users with cognitive disabilities, learning disabilities, or those who relied on emerging assistive technologies.

Moreover, WCAG 1.0's binary approach to compliance—where checkpoints were either met or not—did not allow for varying degrees of accessibility. This lack of flexibility made it difficult for developers to understand how to prioritise accessibility improvements or to recognise when partial compliance could still significantly enhance the user experience.

As the internet continued to grow, the limitations of WCAG 1.0 became increasingly evident. The rise of multimedia content, dynamic web applications, and the diverse needs of a global user base highlighted the need for more comprehensive and adaptable accessibility standards. These challenges set the stage for the development of WCAG 2.0.

WCAG 2.0: Expanding and Refining Accessibility Standards

The Introduction of WCAG 2.0

Nearly a decade after the release of WCAG 1.0, the W3C introduced WCAG 2.0 in December 2008. This new version represented a significant evolution in web accessibility standards, addressing many of the shortcomings of its predecessor while introducing a more flexible and comprehensive framework.

WCAG 2.0 was developed in response to the rapidly changing technological landscape. The internet had become more complex, with the widespread adoption of multimedia elements, advanced web applications, and a growing variety of devices used to access the web. The guidelines needed to keep pace with these developments to remain relevant and effective.

Key Features of WCAG 2.0

One of the most notable changes in WCAG 2.0 was the shift from "checkpoints" to "success criteria." This change reflected a move away from the simple checklist approach of WCAG 1.0 towards a more nuanced system that allowed for varying levels of compliance. The success criteria in WCAG 2.0 were organised into three levels of conformance: A, AA, and AAA.

- Level A represents the minimum level of accessibility, covering the most basic web accessibility features. Websites that meet Level A criteria are accessible to some users but may still pose significant barriers to others.

- Level AA includes additional success criteria that address the major barriers to accessing web content for people with disabilities. Meeting Level AA ensures that content is accessible to a broader range of users.

- Level AAA is the highest level of conformance, requiring websites to meet the most stringent accessibility criteria. However, it is recognised that not all content can conform to AAA standards, and therefore it is considered an ideal rather than a requirement.

In addition to the success criteria, WCAG 2.0 introduced four guiding principles that provided a more holistic approach to accessibility. These principles, often referred to by the acronym POUR, are:

- Perceivable: Information and user interface components must be presented to users in ways they can perceive. This includes providing text alternatives for non-text content, ensuring that content can be adapted to different formats, and making it easier for users to see and hear content.

- Operable: User interface components and navigation must be operable. This principle ensures that all functionality is accessible via a keyboard, that users have enough time to read and use content, and that users can avoid and correct mistakes.

- Understandable: Information and the operation of the user interface must be understandable. This principle focuses on making text content readable and understandable, ensuring that web pages appear and operate in predictable ways, and helping users avoid and correct mistakes.

- Robust: Content must be robust enough to be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. This principle aims to maximise compatibility with current and future tools used by people with disabilities.

These principles provided a clear and comprehensive framework that guided developers in making their content accessible across a range of devices and platforms. They also addressed some of the key limitations of WCAG 1.0 by emphasising the importance of flexibility and user-centred design.

The Impact of WCAG 2.0

WCAG 2.0 had a profound impact on web accessibility, influencing both industry practices and regulatory standards around the world. Many countries, including those in the European Union and the United States, adopted WCAG 2.0 as the basis for their accessibility regulations. For example, the European Parliament's (2016) directive on the accessibility of public sector websites explicitly references WCAG 2.0, mandating compliance with these guidelines as a minimum standard.

The introduction of success criteria and conformance levels in WCAG 2.0 provided developers with more clarity and flexibility in implementing accessibility features. This approach allowed for incremental improvements, enabling organisations to prioritise accessibility enhancements based on their resources and user needs. As a result, WCAG 2.0 facilitated the development of a more accessible internet, where content could be tailored to meet the needs of a diverse user base.

However, WCAG 2.0 also faced challenges. The guidelines were more complex than those of WCAG 1.0, making them difficult for some developers to interpret and implement. Studies have shown that the application of WCAG 2.0 can be inconsistent, with different auditors arriving at varying conclusions about compliance (Brajnik et al., 2012). This inconsistency highlighted the need for clearer guidance and more practical tools to support developers in achieving accessibility goals.

Moreover, while WCAG 2.0 provided a robust framework for technical and design aspects of web accessibility, it did not fully address the content and context in which users interacted with web pages. The focus on system and presentation aspects, rather than content itself, meant that some user needs were not adequately met, particularly those with cognitive disabilities or those requiring more context-specific accessibility solutions.

WCAG 2.1: Addressing Emerging Technologies and User Needs

The Development of WCAG 2.1

As technology continued to evolve and new devices and interfaces became commonplace, the need for updated accessibility guidelines became evident. In June 2018, the W3C released WCAG 2.1, a revision that built upon WCAG 2.0 while addressing the challenges posed by emerging technologies. WCAG 2.1 was developed to fill the gaps in WCAG 2.0, particularly in areas related to mobile accessibility, touch interfaces, and the needs of users with cognitive and learning disabilities.

WCAG 2.1 was not intended to replace WCAG 2.0 but rather to extend it. All the success criteria from WCAG 2.0 were retained, with additional criteria added to address new user needs. This approach ensured that WCAG 2.1 remained backward compatible with WCAG 2.0, allowing organisations to adopt the new guidelines without having to overhaul their existing accessibility efforts.

Key Features of WCAG 2.1

WCAG 2.1 introduced 17 new success criteria, organised under the same POUR principles as WCAG 2.0. Some of the key areas of focus in WCAG 2.1 included:

- Mobile Accessibility: With the widespread use of smartphones and tablets, website accessibility on mobile devices became a crucial consideration. WCAG 2.1 introduced success criteria related to screen orientation, touch targets, and the accessibility of gestures and touch-based interactions.

- Cognitive and Learning Disabilities: WCAG 2.1 addressed the needs of users with cognitive and learning disabilities by introducing success criteria that focused on the clarity and simplicity of content, the predictability of user interface components, and the reduction of distractions.

- Colour and Contrast: Building on the colour and contrast requirements in WCAG 2.0, WCAG 2.1 introduced additional criteria to ensure that users with low vision or colour vision deficiencies could perceive and interact with content effectively.

These new success criteria helped to bridge the gap between WCAG 2.0 and the modern web, ensuring that accessibility standards kept pace with technological advancements and the diverse needs of users.

The Impact of WCAG 2.1

WCAG 2.1 had a significant impact on web accessibility, particularly in the areas of mobile and cognitive accessibility. The guidelines provided clear and actionable steps for developers to create content that was accessible across a wide range of devices and user interfaces. By addressing the needs of users with cognitive and learning disabilities, WCAG 2.1 also expanded the scope of web accessibility, making the web more inclusive for all users.

However, the introduction of new success criteria in WCAG 2.1 also posed challenges for developers and organisations. Implementing the new criteria required additional resources and expertise, particularly in areas such as mobile accessibility and cognitive accessibility. Moreover, the backward compatibility of WCAG 2.1 with WCAG 2.0 meant that organisations needed to ensure compliance with both sets of guidelines, further complicating the implementation process.

Despite these challenges, WCAG 2.1 was widely adopted as the new standard for web accessibility, with many organisations and regulatory bodies incorporating the guidelines into their accessibility policies and practices.

WCAG 2.2: Further Enhancements and Refinements

The Development of WCAG 2.2

Following the release of WCAG 2.1, the W3C continued to refine and expand the guidelines to address additional user needs and technological developments. WCAG 2.2, expected to be finalised in 2023, builds upon the foundations of WCAG 2.0 and 2.1, introducing new success criteria to enhance accessibility further.

The development of WCAG 2.2 has been informed by feedback from practitioners, researchers, and users, as well as by the ongoing evolution of web technologies. The new guidelines aim to address specific accessibility gaps identified in WCAG 2.1, particularly in areas such as navigation, authentication, and the needs of users with cognitive and learning disabilities.

Key Features of WCAG 2.2

WCAG 2.2 introduces several new success criteria, focusing on enhancing accessibility for users with cognitive disabilities, improving navigation and orientation, and addressing the challenges of secure and accessible authentication. Some of the key areas of focus in WCAG 2.2 include:

- Accessible Authentication: WCAG 2.2 introduces success criteria aimed at making authentication processes more accessible. This includes ensuring that users can log in to websites and applications without relying solely on memory, which can be a barrier for users with cognitive disabilities.

- Navigation and Orientation: WCAG 2.2 includes new success criteria that focus on improving the navigability and orientation of web content. This includes ensuring that users can easily find their way around a website, understand their location within the site, and access essential information without unnecessary barriers.

- Enhanced Focus Indicators: Building on the focus indicator requirements in WCAG 2.1, WCAG 2.2 introduces additional criteria to ensure that users can easily identify and navigate to interactive elements on a page, particularly when using a keyboard.

These enhancements in WCAG 2.2 reflect the ongoing commitment to making the web more accessible and inclusive for all users, particularly those with cognitive disabilities and those who rely on assistive technologies for navigation and interaction.

The Impact of WCAG 2.2

The new success criteria in WCAG 2.2 address some of the most pressing accessibility challenges facing users today, particularly in areas such as authentication and navigation. By focusing on the needs of users with cognitive disabilities and improving the overall user experience, WCAG 2.2 aims to make the web more inclusive and accessible for all.

Despite these challenges, the ongoing evolution of the WCAG guidelines underscores the importance of continuous improvement in web accessibility. By adopting and implementing WCAG 2.2, organisations can ensure that their digital content remains accessible and inclusive for all users, regardless of their abilities or the devices they use.

UK Public Sector Bodies Accessibility Regulations

The Introduction of the Accessibility Regulations

To complement the WCAG guidelines, the UK has introduced specific legislation to ensure that public sector websites and mobile applications are accessible to all users. The Public Sector Bodies (Websites and Mobile Applications) (No. 2) Accessibility Regulations 2018 came into force in September 2018, mandating that all public sector websites and mobile apps comply with the accessibility standards set out in WCAG 2.1 AA.

The regulations were introduced in response to the European Union (EU) Directive on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies. The directive, adopted in 2016, aimed to harmonise accessibility standards across EU member states and ensure that public sector digital content was accessible to people with disabilities. Post-Brexit, this legislation has now been renewed to ensure future WCAG updates are applied across public sector websites as soon as available, further enhancing accessibility.

Key Requirements of the Accessibility Regulations

The UK Accessibility Regulations require public sector bodies to take specific steps to ensure that their websites and mobile apps are accessible (GDS 2018). These steps include:

- Compliance with WCAG 2.2 AA: Public sector websites and mobile apps must meet the WCAG 2.2 AA standard as a minimum (as of July 2024). This includes ensuring that content is perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust, as defined by the POUR principles.

- Accessibility Statements: Public sector bodies must publish an accessibility statement on their websites and mobile apps, detailing the level of compliance with WCAG 2.1 AA and any areas where the content does not fully meet the standards. The statement must also provide information on how users can report accessibility issues or request alternative formats.

- Monitoring and Enforcement: The regulations require regular monitoring of public sector websites and mobile apps to ensure compliance with the accessibility standards. The UK Government Digital Service (GDS) is responsible for overseeing this process and can take enforcement action against organisations that fail to comply with the regulations.

The Impact of the Accessibility Regulations

The introduction of the UK Accessibility Regulations has had a significant impact on public sector organisations, requiring them to prioritise accessibility in their digital content and services. By mandating compliance with WCAG 2.2 AA, the regulations have helped to raise awareness of accessibility issues and drive improvements in the design and development of public sector websites and mobile apps.

However, the regulations also present challenges for public sector bodies, particularly those with limited resources or expertise in accessibility. Ensuring compliance with WCAG 2.2 AA can require significant investment in training, tools, and testing, as well as ongoing maintenance and updates to digital content.

Despite these challenges, the UK Accessibility Regulations represent an important step forward in making digital content more accessible and inclusive for all users. By aligning with the WCAG guidelines, the regulations ensure that public sector websites and mobile apps are designed with accessibility in mind, helping to remove barriers and improve the user experience for people with disabilities.

WCAG 3.0: The Future of Web Accessibility

The Evolution Towards WCAG 3.0

As the web continues to evolve, so too must the standards that guide its accessibility. WCAG 3.0, currently in draft form and expected to be fully published in 2024, represents the next major step in the evolution of web accessibility guidelines. This new version aims to address the limitations of both WCAG 1.0 and WCAG 2.0 while providing a more user-centred and outcome-focused approach to accessibility.

The development of WCAG 3.0 has been informed by extensive feedback from practitioners, researchers, and users, as well as by advances in technology and changes in how people interact with digital content. The new guidelines reflect a broader understanding of accessibility, one that goes beyond technical compliance to consider the overall user experience.

Key Features of WCAG 3.0

WCAG 3.0 introduces several significant changes that distinguish it from its predecessors. One of the most notable changes is the shift from a success-criteria-based approach to an outcomes-based approach. This shift moves away from the checkbox mentality of earlier versions, focusing instead on the real-world impact of accessibility features on users.

The new guidelines are designed to be more flexible and adaptable to different contexts, with an emphasis on functional outcomes rather than prescriptive technical requirements. This approach allows for greater innovation and creativity in achieving accessibility, while still ensuring that the needs of users with disabilities are met.

WCAG 3.0 also introduces a new scoring system that allows for more granular evaluation of accessibility. This system enables automated tools to assess and compare the accessibility of different websites and applications, making it easier for organisations to identify areas for improvement and track their progress over time.

In addition to these changes, WCAG 3.0 places a greater emphasis on the user experience, with guidelines that focus on usability, content quality, and the overall effectiveness of accessibility features. The new guidelines also aim to be more accessible to non-technical audiences, with plain language explanations and practical examples that make it easier for organisations to understand and implement the standards.

The Impact of WCAG 3.0

WCAG 3.0 represents a significant shift in the approach to web accessibility, with a focus on outcomes and user experience rather than strict technical compliance. This change has the potential to make the web more accessible and inclusive for all users, particularly those with disabilities.

However, the implementation of WCAG 3.0 will also require organisations to adapt to the new guidelines and update their existing accessibility practices. This may involve investing in new tools and technologies, conducting user research to understand the needs of different user groups, and redesigning content and interfaces to meet the new standards.

As with previous versions of the guidelines, the success of WCAG 3.0 will depend on the willingness of organisations to embrace the new approach and commit to ongoing improvements in accessibility. By adopting WCAG 3.0, organisations can ensure that their digital content is accessible, usable, and inclusive for all users, regardless of their abilities or the devices they use.

The Ongoing Evolution of Web Accessibility

The evolution of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines from WCAG 1.0 to WCAG 3.0 reflects the changing nature of the web and the increasing importance of accessibility in the digital age. Each version of the guidelines has built upon the strengths and addressed the limitations of its predecessors, resulting in a more comprehensive and user-centred approach to web accessibility.

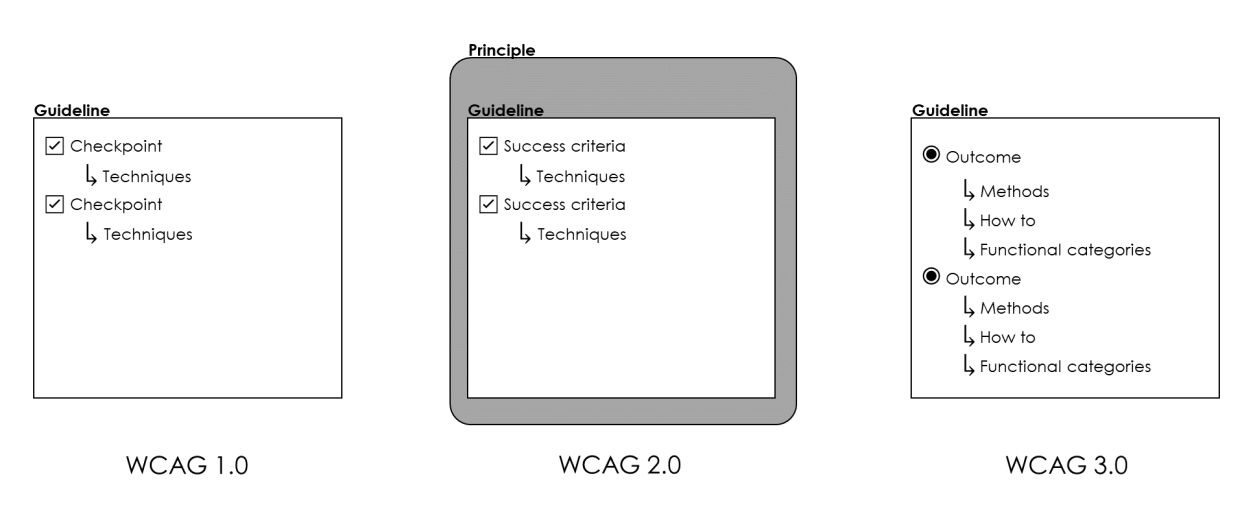

While WCAG 1.0 laid the foundation for accessibility with its checklist approach, WCAG 2.0 and its subsequent revisions (WCAG 2.1 and WCAG 2.2) expanded the scope of the guidelines to address the needs of a diverse user base and the challenges posed by new technologies. WCAG 3.0, with its outcomes-based approach and emphasis on user experience, represents the next step in this ongoing evolution, offering a more flexible and effective framework for achieving accessibility. The diagram below shows the evolution between WCAG approaches:

Visual comparison of WCAG evolution. Reproduced from Muirhead (2022, p.52).

Visual comparison of WCAG evolution. Reproduced from Muirhead (2022, p.52).

As the web continues to evolve, the need for accessible content and inclusive design will only become more important. By staying informed about the latest developments in web accessibility standards and implementing best practices, organisations can ensure that their digital content is accessible to all users, helping to create a more inclusive and equitable online environment.

Summary

Even with the updates brought by WCAG 2.2, it still falls short of delivering fully accessible and usable content for everyone. While the guidelines address the use of assistive technologies, they often rely on idealised user scenarios rather than reflecting the real-world behaviours of diverse users (Kreps & Goff, 2015). As a result, developers who implement WCAG-compliant websites can't simply rely on the guidelines alone—they must also conduct thorough user testing and stay informed about industry best practices to truly meet the needs of their audience. This challenge highlights a shift towards the third wave of human-computer interaction, where focusing solely on metrics and task completion isn't enough to create a seamless and inclusive user experience (Bødker, 2006; Cooper et al., 2012). In today’s complex digital landscape, understanding how users interact with content in various contexts is crucial, and developers must go beyond compliance to ensure that their websites are truly accessible and user-friendly for all (Sloan & Kelly, 2011).

Adapted from Muirhead (2022, pp.52–56).

References

Bødker, S. (2006). When second wave HCI meets third wave challenges. Proceedings of the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Changing Roles (pp. 1-8). https://doi.org/10.1145/1182475.1182476

Brajnik, G., Yesilada, Y., & Harper, S. (2012). Is accessibility conformance an elusive property? Proceedings of the 13th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility.

Cooper, M., Sloan, D., Kelly, B., & Lewthwaite, S. (2012). A challenge to web accessibility metrics and guidelines: Putting people and processes first. Proceedings of the International Cross-Disciplinary Conference on Web Accessibility.

Ellcessor, E. (2010). Bridging disability divides: The development of web accessibility standards in the United States and European Union. Information, Communication & Society, 13(3), 289-308.

European Parliament. (2016). Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies. Official Journal of the European Union.

Government Digital Service. (2018). Understanding accessibility requirements for public sector bodies. gov.uk. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/accessibility-requirements-for-public-sector-websites-and-apps

Kreps, D., & Goff, M. (2015). Code in action: Closing the black box of WCAG 2.0, A Latourian reading of Web accessibility. First Monday, 20(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i9.6166

Muirhead, J. (2022). Informative web content guidelines: A practitioner model for online content effectiveness. (Thesis). University of Salford. Available online: https://salford-repository.worktribe.com/output/1327167/informative-web-content-guidelines-a-practitioner-model-for-online-content-effectiveness

Sloan, D., & Kelly, B. (2011). Web accessibility: An ongoing journey, not a destination. Journal of Web Librarianship, 5(2), 144-158.